STANDING ROOM ONLY FOR CREDIT PLATFORMS.

As corporate bond trading platforms do battle, the size of the prize is not clear. Joel Clark reports.

How much profit can a credit trading venue actually make? Getting a new trading platform off the ground is not easy even in transparent asset classes. Chi-X Europe made just £800,000 in 2010, three years after its launch, when it was processing 17% of the secondary equity market in Europe. The following year it was bought by BATS Europe, then the continent’s second largest multi-lateral trading facility, for US$300 million after BATS had posted a US$3.8 million loss in 2010.

The drivers may be different in 2016, but a similar story is playing out in corporate credit, where post-crisis liquidity concerns have led to a plethora of platforms battling for market share. The bond market cannot ultimately sustain so many platforms, underlining the need for unique business models that can attract and retain a viable community of users.

“My sense is that most participants are sticking with the incumbents at the moment, but there is a slow migration to some of the new all-to-all initiatives. In the long term there will only be a few survivors, and a lot will depend on the strength of platforms’ connectivity into existing buy-side workstations,” says Lee Sanders, head of FX and fixed income trading at AXA Investment Managers.

“My sense is that most participants are sticking with the incumbents at the moment, but there is a slow migration to some of the new all-to-all initiatives. In the long term there will only be a few survivors, and a lot will depend on the strength of platforms’ connectivity into existing buy-side workstations,” says Lee Sanders, head of FX and fixed income trading at AXA Investment Managers.

Assessing the long-term viability of credit platforms is difficult. Many operate as new initiatives of large, well-established entities. Much will depend on how much capital those entities are willing to commit to platforms before they become profitable – the ‘burn rate’. If a platform miscalculates the money needed and is unable to negotiate for more capital it can collapse as was seen with Bondcube after just three months in 2015.

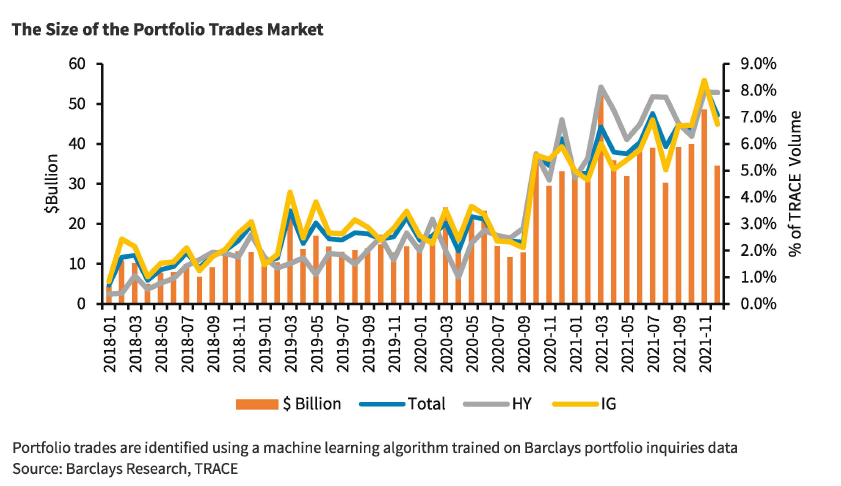

The size of the market

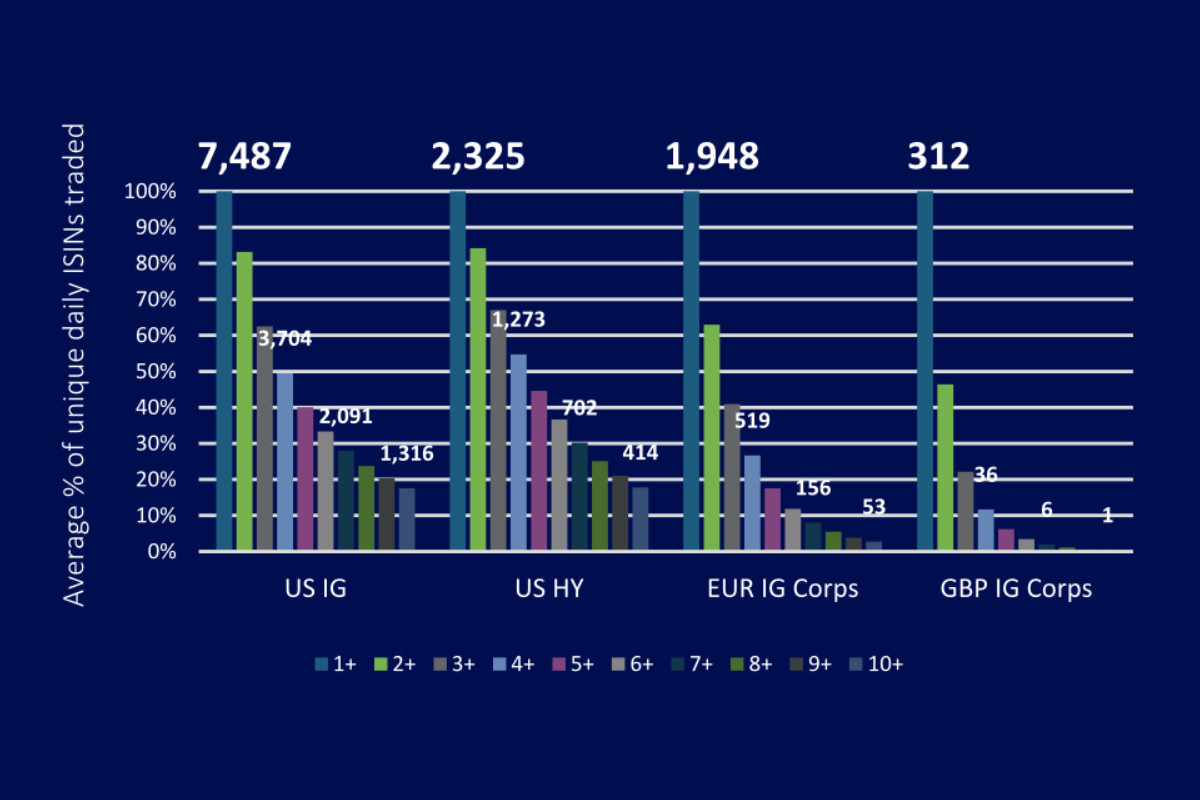

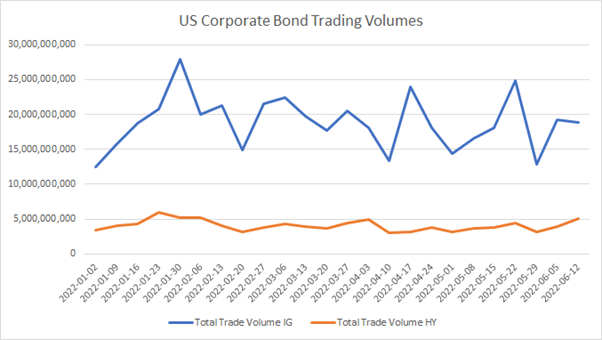

Data compiled by SIFMA from the TRACE reporting hub records average daily volume in US investment grade and high yield bonds at $32.3 billion (E29 billion) this year or E1.8 trillion a quarter. Trax estimated the volume of European corporate bond trading Q1 2016 at E498 billion.

However this is not the full picture for trading platforms. Firstly, the cut they get is out of the electronically traded side. For investment grade bonds in Europe that is 46% and in the US 20%, according to research firm Greenwich Associates. So based on raw numbers that gives a trading volume of E828 billion in US and E229 billion in Europe per quarter – roughly E1 trillion per quarter – to be fought over in IG.

Amar Kuchinad, chief executive officer, at US credit trading platform Electronifie believes there are additional trading opportunities that can be unlocked that are not getting executed currently.

Amar Kuchinad, CEO, Electronifie

Amar Kuchinad, CEO, Electronifie

“We don’t view the current revenues of electronic platforms as the wallet we are pursuing,” he says. “Customers pay approximately US$3 billion in transaction costs each year to buy bonds that other customers have sold on the same trading day. That is the total current wallet we think electronic platforms can participate in, even if the price for each transaction is lower.”

Credit venues and traders do not take a commission on trades as in equity markets so volumes are only part of the story for estimating revenues. There is considerable variation in fee structures at present. Larger platforms like Tradeweb and MarketAxess charge an annual fee to the sell side – reported by traders to be anywhere from several hundreds of thousands up to over US$1 million, depending upon the instruments and geography – with further charges for volume set by X hundred dollars per million traded, based on the instrument’s liquidity.

In the majority of cases, dealers have traditionally paid the bill for platform access. As their ability to make prices falls away and buy-side firms increasingly make prices, that commercial model will have to be reformed.

“In a traditional principal market-making model, clients would be charged by dealers as part of the spread and platforms would bill the banks on a per-ticket basis, but as the market has evolved and moved away from principal market making as the only model, it makes sense to charge liquidity takers directly, as we do in Open Trading, whether they are dealers or clients,” says Gareth Coltman, head of European product management at MarketAxess.

Buy-side crossing network Bloomberg charges an undisclosed commission to both parties. However explicit commission or taking a cut from the spread are not the only options. Bloomberg, for example, makes no additional charge for trade execution beyond the fixed cost of the terminal itself – prompting one dealer to call it “The most expensive free trading you can get”, while other platforms charge users on a monthly basis.

Kuchinad says, “The opportunity for new platforms is less about taking away volumes from other platforms and dealers and more about allowing a greater volume of trades to happen.”

New ideas

Despite the diversity of fee structures available today, certain practices may become less viable in the future. Charging on a per-ticket basis, for example, makes it difficult to increase revenue when trading volume is low, while an individual user charge could become less sustainable as sell-side headcount falls.

For many platforms, however, building support among a community of like-minded participants is likely to be a greater priority at this stage than turning a profit and growing revenue immediately.

“All-to-all platforms may need to keep their commercial models fairly flexible initially, so that they can vary the way in which they levy trading fees on their users in the future as a means of incentivising them to do more volume when the business model is properly scaled, in terms of the number of users and sizeable enough trading volumes to justify growth and, subsequently, higher trading fees,” says Russell Dinnage, lead consultant at GreySpark Partners.

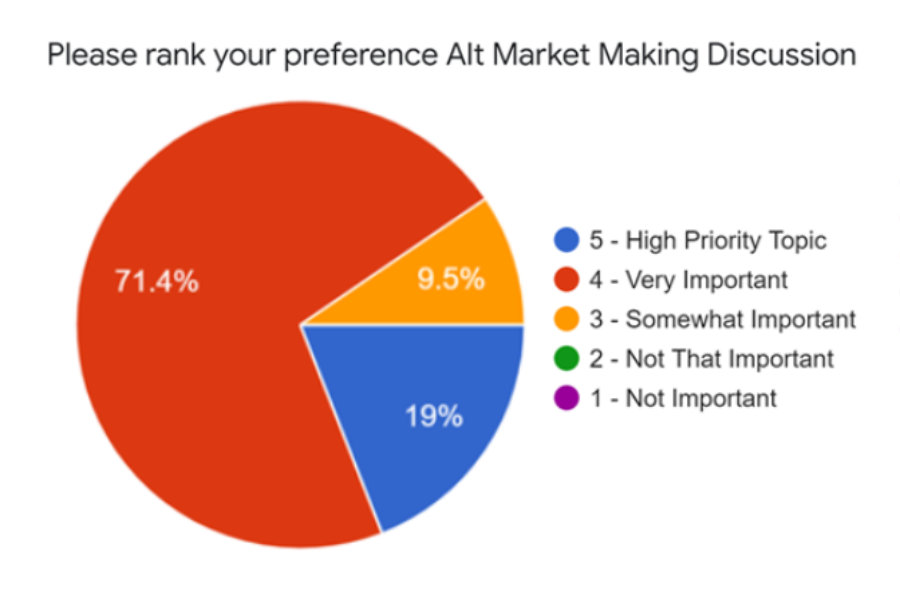

It may be early days, but industry surveys certainly indicate a growing appetite to explore alternative trading venues. Price improvement, access to new liquidity providers and an interest in all-to-all trading were all widely cited by respondents to a Greenwich Associates study in late 2015 as key criteria in selecting a bond trading platform.

“Platform fees tend to be a fraction of the bid/offer charged by market-makers, so protocols that increase competition tend to provide far greater savings than the platform fees,” says Kuchinad. “For example, one electronic platform claims all-to-all trading saves approximately five basis points in yield vs. traditional customer-to-dealer protocols.”

Incumbents can also tap the need to change protocols. MarketAxess, for example, has built a strong position in US investment grade and high yield corporate bonds through its Open Trading offering, launched in 2013. Volume hit a record $37 billion in the first quarter of 2016, up from $18 billion in the first quarter of 2015. The number of liquidity providers grew from 346 to 527 firms during that time.

“Where there has been success on the newer platforms, it seems that the liquidity is additive, rather than taking market share away from MarketAxess and the other incumbents. New entrants are plugging directly into buy-side desktops and driving trading that may not otherwise have taken place,” says Kevin McPartland, head of research for market structure and technology at Greenwich Associates.

Early success

New platforms are making inroads. Liquidnet’s equities platform has roughly $80 billion of global liquidity and achieves a match rate of around 20% each day, while its fixed income platform, launched in October 2015, is currently achieving around $8 billion a day and targeting a 5% match rate – a level it expects to reach in the future as more members join.

“Liquidity is more fragmented in fixed income, so our match rate will be lower than in equities, but this will increase as our membership grows. We are working closely with individual firms and technology vendors to integrate with buy-side order management systems. This is key to growing liquidity and improving user experience,” says Mark Pumfrey, head of Europe, the Middle East and Africa at Liquidnet.

“Liquidity is more fragmented in fixed income, so our match rate will be lower than in equities, but this will increase as our membership grows. We are working closely with individual firms and technology vendors to integrate with buy-side order management systems. This is key to growing liquidity and improving user experience,” says Mark Pumfrey, head of Europe, the Middle East and Africa at Liquidnet.

UBS Bond Port proved highly popular with buy-side traders in The DESK’s ‘Trading Intentions Survey 2016’ having been relatively unnoticed in 2015, and its low cost for users is said to be a big part of the attraction. Long-term viability is likely to be determined not only by the popularity of particular trading protocols and commercial models with end users, but also by the level of investment platforms are willing to make in connectivity to existing trading infrastructure.

“Building a new network is very difficult, both in terms of the underlying technology and the time it takes to build the essential connectivity into dealer and client platforms. Given the growing need to focus on regulatory projects, it seems that the window of investment in trading platforms is closing,” says Coltman.

However it is the capacity to make a difference to buy-side alpha-generating opportunities that Kuchinad believes will prove a platform’s value. “Transaction costs have a big impact on investing strategies. One client has told us that absent transaction costs, their portfolio model might suggest – for example – US$1 billion of trades to attain an optimally-allocated portfolio, but once transaction costs are factored in, the model only has US$200 million of trades that are still economically optimal.”

©TheDESK 2016