Market volatility may shift rates back to voice in 2019

If predicted volatility pushes firms towards voice trading next year, rates traders will suffer from a heavier administrative burden. Dan Barnes reports.

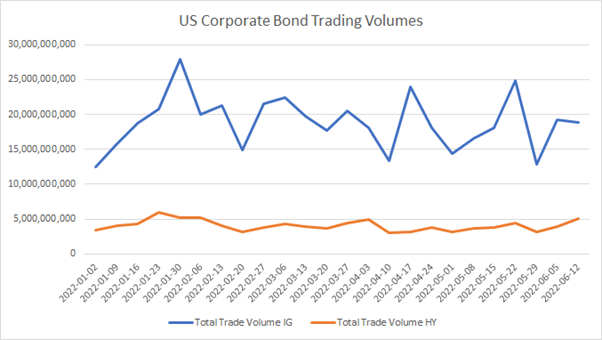

The effectiveness of electronic trading in supporting liquidity is likely to be tested in the next 12 months. Quantitative easing purchases by the European Central Bank (ECB) will decline towards zero in 2019 (see Fig 1). Matt King, credit products strategist at Citi warned in a July 2018 presentation that risk assets particularly will find themselves jarred by price movements as marginal buyers, such as central banks, step back from the market.

“In the short term, in general when markets get volatile there will be a move to voice as that will give more adequate pricing,” says Hans Bayer, principal trader at NN Investment Partners. “You may even move more to non-comp for prices if that fits the trade.”

Government bond markets in Europe have historically had the highest relative levels of electronic trading, averaging 56.6% by volume between 2015 and 2017, according to analyst firm Greenwich Associates. Regulators have been encouraging its growth across markets, in order to create a more transparent and structured process. As a result, the rates market would see the most marked change in execution style in choppy waters.

“If you look at Italian bond futures, the book is so thin that it has become pretty unreliable,” says Bayer. “It has always been more volatile, and it is hard for banks to put big positions on, so in those markets voice trading is more appropriate.”

It is hard to separate the value that electronic trading provides in delivering more consistent fills for orders, from the markets’ natural liquidity. Citi’s King noted, “Govies are good at finding new buyers” and electronic execution is a catalyst, not an engine, for trading.

“The problem is that the electronification of the market is only applied in areas where the market is already liquid,” says Gianluca Minieri, chief executive officer at Amundi Intermédiation, the trading function for asset manager Amundi. “So I have no doubt that electronic trading drives best execution, but I have more doubt that it increases access to liquidity.”

‘Electronic’ in this case usually means trading via an electronic venue, either a dedicated trading platform or via electronic protocols rather than voice. The request-for-quote (RFQ) model, in which prices are requested from dealers and/or other asset managers is the most common protocol, although auction and central limit order books are also used.

“Whether electronic trading improves the quality of execution depends on what determines best execution for a given order,” says one senior fixed income trader at a UK asset manager. “If speed to market is important because things are moving quickly, then you could argue that physically asking three brokers in competition (‘in comp’) to provide prices might be slower. So if speed is a priority, you could argue that quality of execution is improved using a platform.”

However, electronic trading does not guarantee a better price than a voice trade. Execution quality is affected by market liquidity and activity.

Bayer says, “If you keep on trading electronically in a market where prices are collapsing, you may not be trading at prices that are realistic.”

The transparency provided by trading on a platform can be a problem. If a broker-dealer takes the other side of a client’s trade and that is visible to other banks, the banks may offer at a lower price knowing the broker is a seller.

If a desk trades for retail funds, they will have very public in-flows and outflows, making it easier for counterparties to know if they are a buyer or seller and buy or sell the bonds ahead of the asset manager. As a result they may have to be more reactive to axes offered by dealers instead of going out into the market on an RFQ basis. Voice also enhances feedback and negotiation.

“By voice trading you may be able to counter a bit more; for example Bloomberg doesn’t have a countering function to improve on a bid or offer,” noted one buy-side trader. “You get more colour. But if you only have a few dealers then the volume of activity over voice might leave them stretched, so electronic helps them focus their efforts.”

Heavy lifting

An indirect impact that electronic trading has on execution quality is that of freeing up of time.

“The increase in electronic trading is clearly bringing improvements to the overall trading process,” says Minieri. “Technology has enabled banks and buy-side dealers to reduce costs through automation. It has allowed us dealers to better identify the dynamic of trading flows coming from their clients and how these flows change vis-a-vis market conditions.”

If a venue captures and reports a trade, it can make the processing of a trade far more efficient. The value of reducing workload on the buy-side trading desk cannot be underplayed. The reporting requirements of the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID II) which came into effect on 3 January 2018 have added a considerable, administrative burden to traders. Due to the nature of best execution reports, which at some firms will require the instructions from portfolio managers being manually noted down, the time to process a trade has increased considerably.

Electronic trading also provides better data points such as timestamps that are captured so that supports execution analysis.

Having a greater choice in how to execute orders gives traders greater capacity to do their job. In this sense, electronic trading is part of a tool set in addition to voice trading, rather than being a panacea in itself. The interplay between the two can be important.

As one trader, who preferred to remain anonymous, observed, “An order can be tee’d up on the phone and then played out on the platform; for example if there were two brokers in comp, they might be told that an order would be placed on the platform and that provides greater efficiency of booking it in.”

Shift to electronic rates

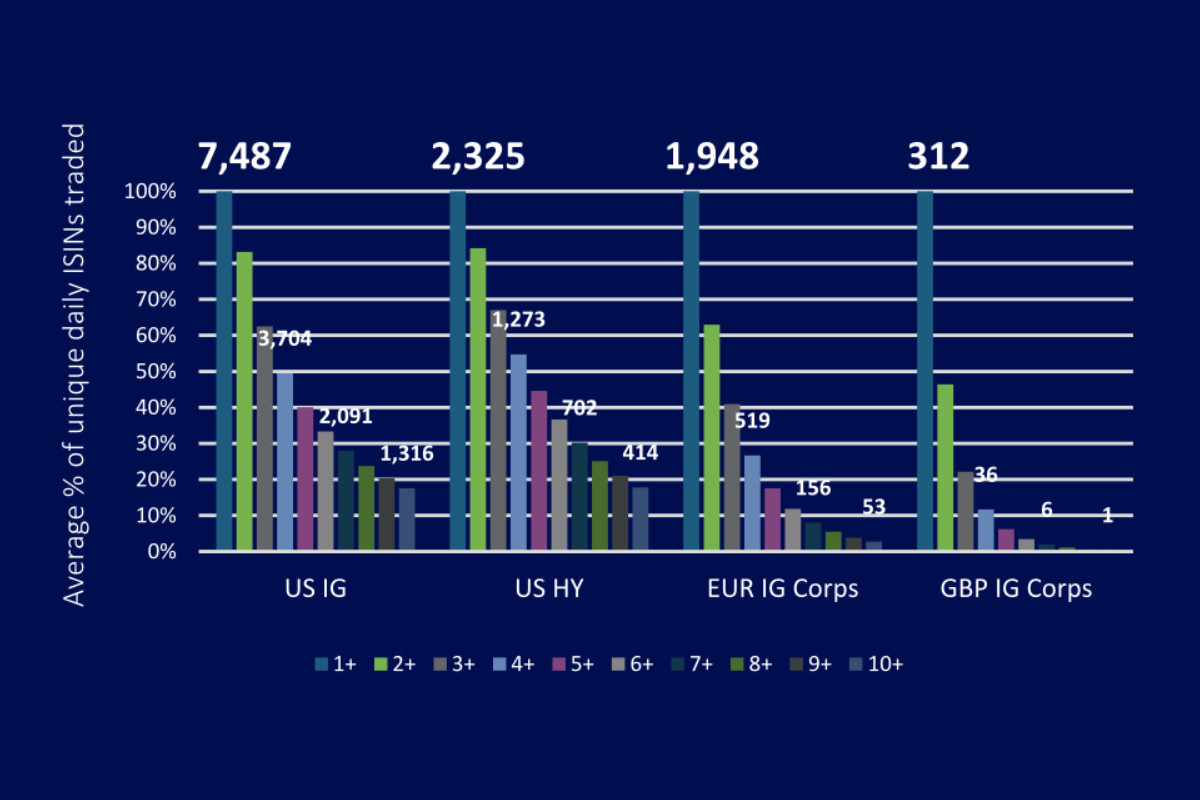

Ostensibly a democratising model, electronic platforms ought to enable asset managers to reach a wider range of brokers, however the data does not support this. Last year, in its analysis of European fixed-income electronic trading, Greenwich Associates’ consultant Tom Jacques observed, “When they do trade electronically, investors gravitate to the market’s biggest dealers.”

In the rates space, electronification has become far more common than in the corporate bond market. The latest figures from Greenwich noted that 52% of volume was conducted via electronic trading.

Although this has largely grown via request-for-quote (RFQ) trading on electronic platforms, in this year’s BENCHmark survey for 2018, The DESK found that the proportion of rates trading conducted via electronic non-RFQ matched the level of voice trading (18%) for the first time (see Fig 3).

“Electronification of trading is also giving greater economies of scale for large asset managers like us, who are capable of internalising more flows efficiently across trading desks and thereby decreasing the competition between internal desks,” says Minieri. “Previously a firm’s London desk may not know what the Singapore desk was doing.”

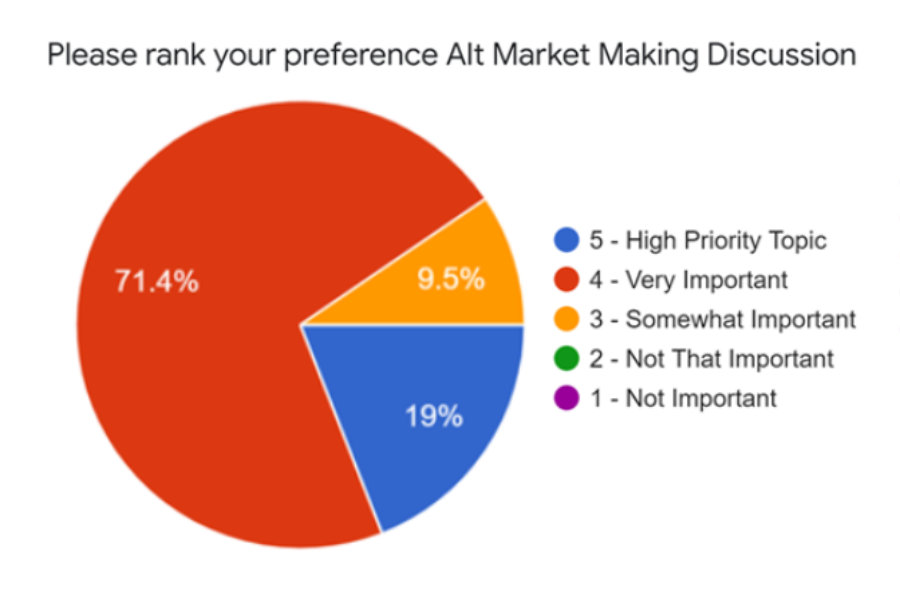

Market makers are no longer the risk bearers they once were, and asset managers may strain to find counterparties at the right price in the event of a big sell-off or a volatile period. Electronic venues can still offer some support in these circumstances, notes Minieri. “The other benefit that platforms bring is the creation of new protocols,” he says. “Big asset managers are the biggest holders of bond inventories, so where platforms are concentrating volume they can develop protocols to allow trading in large sizes, or all-to-all, which unfreezes those huge bond inventories.”

That said, where buy-side firms are moving in the same direction, all-to-all trading is challenged. It may be that voice trading and its associated manual processing, comes to the fore. If that does happen execution quality may not be directly affected, but the strain on desks almost certainly will.

“The turmoil that occurred in May 2018 has not left the markets since then,” says Bayer. “We think that this phenomenon will delay the move to electronic trading but only temporarily – it will not prevent it.”

©TheDESK 2018

TOP OF PAGE