The DESK asks Susan Estes, CEO, OpenDoor Trading LLC., for her insights into the US Treasuries market.

How would you describe the depth and width of liquidity in the US Treasuries market today?

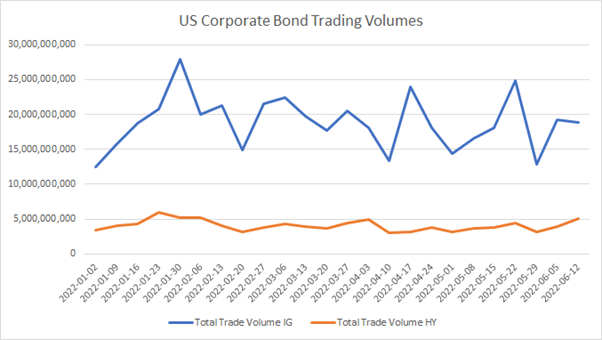

It’s important to recognise that the US Treasury market has two separate and distinct segments with markedly different liquidity profiles: the active, or on-the-run issues, and the off-the runs. The six on-the-run issues account for less than 2% of total notional issuance outstanding, yet they are responsible for over 68% of average daily trading volume.

It is this small slice of the market that is used as evidence to support statements by official institutions that the Treasury market remains healthy. Yet there is little evidence that the remaining 98% of the market – $13-plus trillion of off-the-runs that are held by buy-side, real-money accounts that include the largest pension, sovereign wealth funds, mutual funds, bank portfolios, foreign central banks and the Fed’s SOMA portfolio – enjoy the same amount of liquidity.

The misrepresentation of this liquidity bifurcation is widespread. For example, in May last year, the US Treasury posted a blog which concluded that overall liquidity in 2016 was consistent with historical levels, a view based solely on the 2% of on-the-run data collected from the inter-dealer market. This followed an acknowledgement in the Joint Staff Report of the lack of official data available away from the on-the-runs.

To be fair, the Treasury measures may be consistent with historical levels, but the devil is in the details. For example, average daily trading volume has generally hovered around $475 billion since 2005. However, during that same timeframe the total size of the market more than tripled from $4.1 trillion to the $13.8 trillion it is today. Even after subtracting $2.3 trillion for Fed SOMA holdings, the ratio of market volumes to issuance has collapsed by over 60%.

Off-the-run volumes have been in a general and consistent decline post-crisis. In the past two years alone, off-the-run volumes collapsed by a steep 20% relative to on-the-runs. Given this significant volume retrenchment by a segment that represents 98% total notional issuance outstanding, the only reasonable conclusion that can be reached is that off-the-run liquidity has been severely damaged.

The Treasury referenced other market metrics as well, such as historical bid/ask spreads, the tightness of which is easy to disregard given they also remained very tight during the October Flash Crash, when market liquidity was anything but robust. Trade sizes were also noted to have remained stable, but there is no reasonable way to extrapolate trade size or market impact from electronically-traded on-the-runs to off-the-runs that trade sporadically by voice or RFQ.

Since the blog posting, FINRA has received SEC approval to collect data that should improve this view. Improved transparency to our official institutions is a good thing, but strong evidence of the market’s bifurcation already exists. Any additional denial will eventually result in a loss of credibility, something the US Treasury, the Fed, and the market can ill afford.

What has created the existing liquidity picture in off-the-run Treasuries market?

There are many factors that contributed to the structural problems we are facing. These include three rounds of quantitative easing, during which the Fed increased its holdings in the SOMA portfolio by reducing floating supply in off-the-runs; increased capital requirements and a global effort to reduce risk.

The market dysfunction increased as traditional dealers’ inability to warehouse risk under the new regulations coincided with technological advances that fuelled the growth in high-speed algorithmic trading by unregulated principal trading firms (PTFs). The PTFs account for the most trading and standing quotes in the electronic inter-dealer on-the-run market, although dealers still account for the majority of secondary cash market trading in off-the-runs.

How does that impact buy-side traders’ ability to source liquidity in off-the-runs?

Since dealers dominate market-making in off-the-run Treasuries, and regulatory reform has not only constrained their ability to warehouse risk, but greatly reduced the ROEs of their Treasury trading business, there is less balance sheet available to provide liquidity for the buy side.

I recently read a paper by a senior economist at the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, in conjunction with representatives from both Cornell and Fordham Universities, that stated what most market practitioners are already aware of – that more active investors, with larger holdings of securities, receive better execution in pricing than less active investors, with smaller holdings of securities. While the paper focused on corporate bonds, the same could be applied to the Treasury market. So, while less balance sheet has contributed to increased transaction costs and wider bid-offer spreads for off-the-runs in general, the largest impact is most likely being felt by institutional buy-side investors that lack the influence of the largest participants.

At present which regulations are in play for these markets?

While we can all agree that the Volcker Rule and the Basel capital rules, and in particular the Liquidity Coverage and Net Stable Funding ratios, have been highly impactful, what has recently captured my attention is the Fed and Treasury’s 180-degree reversal on its long-standing position to exempt the market from TRACE reporting.

In the 2015 Joint Staff Report to Congress, the US Treasury, Board of Governors, and FRBNY joined the CFTC, and the SEC, supporting efforts to enhance public reporting for the US Treasury market. This turnaround and conclusion that public reporting is good for the market pre-empted the Treasury’s RFI seeking comment on both more comprehensive official sector access to Treasury market data, as well as the benefits and risks of increased public disclosure of Treasury market activity. It also foreshadowed the SEC’s review of the letters and ultimate authorisation to FINRA.

While I strongly support increased price transparency in the market, I find it disconcerting that the five agencies – all non-market practitioners – determined that public reporting was a good thing and pushed strongly in that direction before the Treasury solicited public comments, and prior to the SEC’s review of those comments. It’s even more disconcerting that the push for real-time, full trade size public reporting is largely a PTF-led phenomenon. Indeed, if you read the PTF comment letters, both individual firms and their representative industry associations, argue aggressively in favour of both. This is a trading community that has very little footprint in off-the-runs and has capital under management measured in the low billions.

By contrast, letters submitted on behalf of real-money buy-side accounts, by their industry associations, whose collective assets under management are measured in trillions, take an exceedingly more cautious approach: they support official data collection but propose notional caps on trade size, delayed time release and exemptions for less liquid, off-the-run securities.

I find it equally interesting, or perhaps equally curious, that when opining on the letters submitted to the Treasury’s RFQ, the SEC chose to reference one very dominant PTF trading firm with $25 billion under management more than any other single contributor. In fact, you have to combine all of the footnotes for the entire community of asset managers, bankers, hedge funds and ETF fund associations to equal the weight of a single PTF.

Under current plans, how will regulations be introduced/changed to affect this market?

The new Administration has denounced much of the financial reform legislation, and President Trump has personally and publicly pledged to repeal Dodd-Frank.

So, where does that get us? If fully repealed, banks would once again be allowed to take principle risk for their own proprietary positions. However, without repeal of the Liquidity Coverage and Net Stable Funding Ratios, allowing proprietary trading without balance sheet relief is tantamount to building a boat in the desert. Given that, I don’t see any significant change in dealers’ current posture in the market.

It’s worth noting that both the Liquidity and Net Stable Funding ratios were not legislated by the United States, but rather by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, a global organisation on which the United States serves as a participating member.

As for TRACE reporting of Treasury trades to FINRA, although it is presently being collected for official eyes only, public reporting appears inevitable. While I believe greater availability of data is beneficial for the market, I would urge caution. The conclusion that public reporting was a solution to a more stable Treasury market was reached in a vacuum, without a reasonable weighting of investors vs trading firm opinions. I believe it is important for market participants to evaluate whether or not there has been a strong bias favouring the opinions of unregulated entities that trade significant volumes but do little to help the US Treasury underwrite debt, over the interests of regulated banks and the investors that have supported the financing of our nation’s ballooning debt.

Where do you see a need for structural reform?

The unintended consequence of regulatory reform has been an increase, not decrease, in market concentration. Per Fed statistics, pre-2008 crisis, the top quintile of primary bank dealers accounted for 40% of total market share in the US Treasury market. Back then, market share was relatively evenly distributed with the top player accounting for 10%. Today, the same measure shows the top quintile now controls 60%. The distribution within the first quintile is also heavily concentrated; the top dealer today commands a 25% market share.

In addition, a single large winner has emerged in the inter-dealer market which facilitates the majority of all fully electronic, on-the-run trades. ICAP’s BrokerTec processes close to 80% of all inter-dealer electronic trading, with NASDAQ’s eSpeed barely holding on in the low 20% range. Such high market share concentration among institutions providing liquidity in, or access to, the largest debt market in the world would appear to be a recipe for disaster.

How are existing trading models coping with liquidity provision?

Ninety percent of all electronic trades in Treasury on-the-runs are executed in one of the two inter-dealer central limit order book, or CLOB, platforms: ICAP’s BrokerTec or NASDAQ’s eSpeed. CLOBs work well for highly liquid on-the-run securities where price discovery is not an issue. However, the inter-dealer market has limited access and is dominated by large bank dealers, PTFs and hedge funds.

In contrast, 95% of electronic market liquidity in off-the-runs is accessed through an RFQ, or request for quote, method. The RFQ model is flawed in the same way multiple telephone inquiries are flawed; by going to say three dealers, the institution exposes its position to more than the winning bank dealer.

Buy and sell inquiries in the same off-the-run issue rarely take place simultaneously or with the same dealer. As a result, the bid-offer spread is wider to compensate the intermediating dealer for warehousing the risk. Given the adverse impact on balance sheet reductions on depth of liquidity, transaction costs have been steadily increasing for off-the-run securities.

To be fair, the RFQ model was not designed to increase liquidity in illiquid securities, but rather to automate record keeping so that evidence of compliance (securing a minimum of three quotes) was collected and auditable for every trade. That made sense in the early 2000’s when off-the-runs traded with the same market depth as on-the-runs, but leaves it ineffective today.

What do you see as a viable solution to the current structural challenges facing the market?

One of the largest structural challenges facing participants in the US Treasury market today is finding and sourcing liquidity in off-the-runs. We have just gone through an entire post-crisis political cycle with a single political administration, and an accommodative monetary authority that ushered in historical low rates. There are traders out there that have never experienced a fully liquid yield curve, across 90% of the 300+ Treasury issues, or a significant tightening cycle. Many of OpenDoor’s senior managers have experienced and traded both. We felt compelled to try to bring a market-based solution to help restore liquidity in the off-the-runs, before the market is challenged with another Black Swan event.

Session-based auctions have proven very successful in restoring liquidity. Emerging markets is one good example, CDS another. It also makes sense for off-the-run Treasuries and TIPS, which is why OpenDoor designed an all-to-all, session-based auction platform specifically for those instruments.

Our team works with incumbent bank dealers to leverage their clearing infrastructure for a seamless front to back experience for the end-user, while providing anonymity during each auction for all participants. During auctions, buy side can match with buy side, sell side with sell side or buy side with sell side. Bringing all participants together on a level playing field at a single point in time, increases the probability of matched trades. The buy side can maintain their dealer relationships as dealers transition a portion of their business from principal risk to riskless principal.

The OpenDoor team is grateful to our Sponsor-dealers and End-Users for participating in the continuous feedback loop that provided the input necessary to deliver a platform that will serve a large and diverse marketplace.