Henry I of England famously died from eating a surfeit of lampreys – a delicacy until consumed to excess. Central banks might want to review that story as they are clearly eating too many bonds distorting the apparent appetite for debt.

Henry I of England famously died from eating a surfeit of lampreys – a delicacy until consumed to excess. Central banks might want to review that story as they are clearly eating too many bonds distorting the apparent appetite for debt.

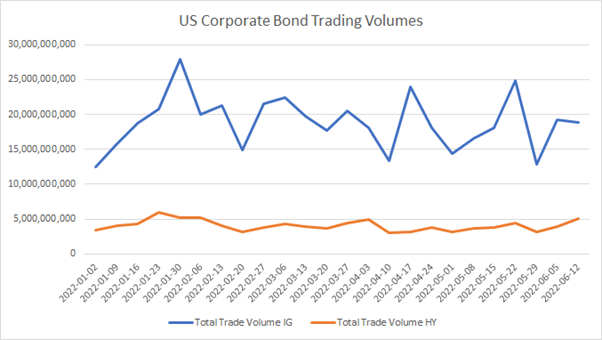

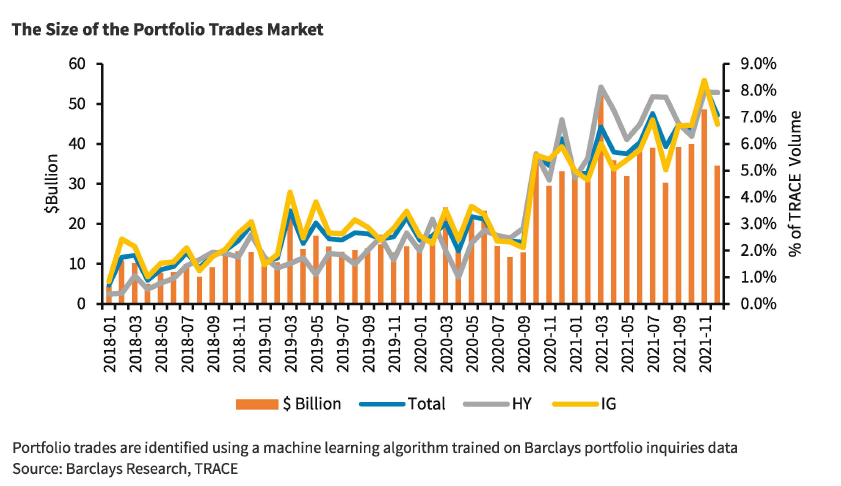

According to Bank of America analysts, US asset issuance has hit an annualised record US$7.4 trillion including US$4.5 trillion of US Treasuries, US$1.8 trillion of investment grade (IG) and US$0.6 trillion of high yield (HY) bonds.

The daily rate of issuance in the US is estimated at US$9.04 billion daily. Year-to-date bond supply has exceeded demand, the analysts note, and S&P recently noted that issuance is at a historically high level, being 35.3% up on 2019, but the appetite for bonds to date is not from investors alone.

For the past six months central banks bought US$10 billion of bonds – globally – every day. While global bond issuance is not recorded, the US constitutes roughly 33% of global debt.

If this back-of-an-envelope calculation is correct, then central banks could have been buying up around 30% of issued debt. They bought 23% of the recent European Union NGEU issuance.

The central banks involved in bond buying now stretch across developed and emerging markets with India, Indonesia and the Philippines all notably engaging in 2020.

What is the concern for traders in fixed income markets? Having a guaranteed buyer in the market distorts both price and liquidity. If market liquidity looks bad today – and both volumes and spreads indicate it does – the ‘real’ market liquidity provided by private market participants is worse.

Issuers are keen to provide bonds to the market (see this week’s article on CUSIP numbers) when central banks are a buyer of last resort and interest rates are low, so it is fair to say that the supply is reflective of issuer confidence.

Central banks are pulling back on QE this year, led by the US Federal Reserve and Reserve Bank of Australia and this may be the proverbial tide going out. When issuers have to fight harder to get a better yield, borrowing costs will rise.

Overall cash levels are high according to S&P analysis but as Government support for COVID-struck businesses declines there are likely to be credit events on the horizon. For all the analysis that accounts for known issues, the occasional corporate fraud or accounting scandal can have significant ramifications.

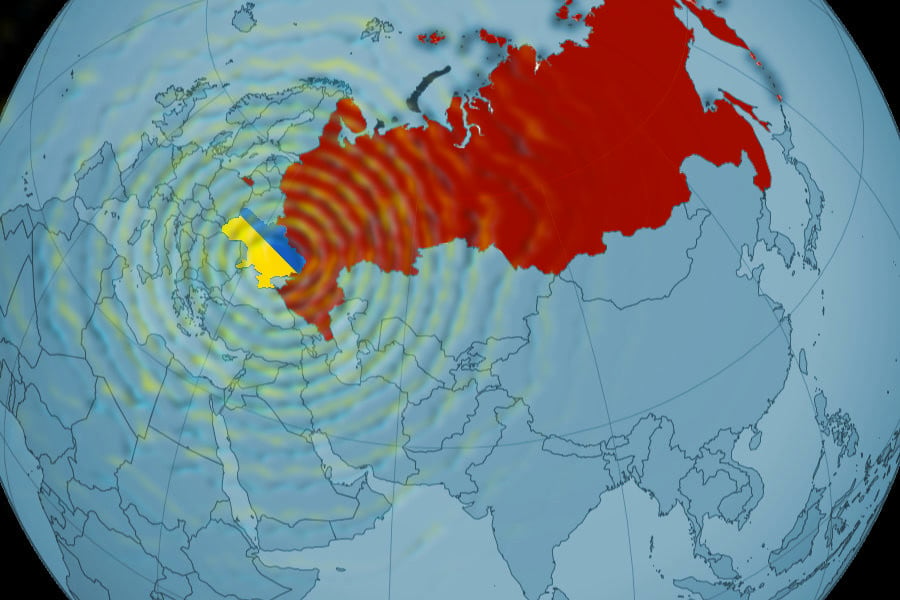

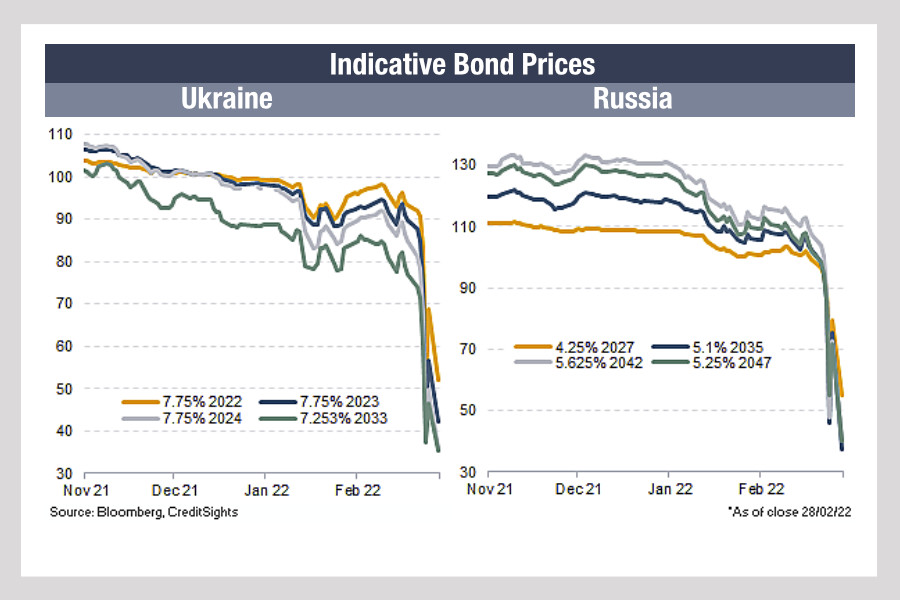

A repeat of last year’s oil war, combined with any other event, could spark another sell-off. Central banks themselves will have to manage their own balance sheets to avoid risk exposure, potentially adding to downward pressure, while investment traders may find that both liquidity and price formation are even worse the second time around.

©Markets Media Europe, 2021

TOP OF PAGE